Hemmings Motor News’ Mike McNessor does a deep dive on SUPERCHARGING BOOSTS FREE HORSEPOWER, starting in 1906!

When you discuss maximizing an engine’s volumetric efficiency, you are: –Boring everybody else at the party (as usual);

When you discuss maximizing an engine’s volumetric efficiency, you are: –Boring everybody else at the party (as usual);

–Explaining to your spouse why it’s crucial that you drop a couple of grand on a supercharger for your sports car;

–Engaging in a 100-plus-year-old quest to get the most out of an internal combustion engine.

If you said all of the above, you’d be correct.

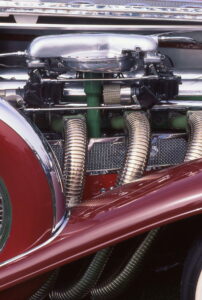

Supercharging was the earliest method used to squeeze more air into an engine than atmospheric pressure could provide naturally — a key to increasing an engine’s volumetric efficiency. Without the pumping action of the supercharger to increase the air pressure and density beyond the level of the atmosphere, the cylinders can’t fill to their maximum volume. But with the aid of a supercharger, they fill to the brim with a pressurized air/fuel charge. Thus, the cylinder displacement “grows” or is at least fully utilized. There is no doubt that SUPERCHARGING BOOSTS FREE HORSEPOWER! Pacers’ Tasmanian Devil Fuel Altered, with GMC/Roots blown & injected Hemi, above.

By harnessing a device that can push more air into an engine, you can add more fuel, make more power, and, voilà, you’re off to the races — literally in the case of the pioneering Chadwick Six (more about that in a moment). Giants and founding fathers of internal combustion recognized this. Rudolf Diesel was an early adopter, as were Louis Renault and Gottlieb Daimler.

By harnessing a device that can push more air into an engine, you can add more fuel, make more power, and, voilà, you’re off to the races — literally in the case of the pioneering Chadwick Six (more about that in a moment). Giants and founding fathers of internal combustion recognized this. Rudolf Diesel was an early adopter, as were Louis Renault and Gottlieb Daimler.

In the U.S., the earliest recorded supercharged competition car started to take shape in 1906. According to a 1976 story in Special Interest Autos, it was that year that John Thomas Nicholls, chief engineer of the Chadwick Engineering Works in Pottstown, Pennsylvania, installed a belt-driven blower on a 1,141-cubic-inch Chadwick six-cylinder engine.

This early centrifugal supercharger was reportedly 10 inches in diameter, and its impeller spun at approximately 20,000 rpm while the massive six thumped along at its 2,200 redline. In 1907, Nicholls upped the boost by running three centrifugal superchargers in series. This three-stage arrangement used impellers with 12 blades each, 10 inches in diameter, each feeding into ducts of progressively smaller diameter.

Chadwick campaigned its supercharged “Big Six” in the 1908 Vanderbilt Cup Race and, according to the October 29, 1908, edition of “The New York Times,” the vehicle “… showed exceptional speed both in practice and in the early part of the race.” Magneto trouble sidelined the Chadwick, according to “The NYT,” but they speculated that it would’ve likely challenged Locomobile for the overall. Hill climbing seemed to be the supercharged engine’s forte, and the Chadwick went on to win the 1908 Wilkes-Barre Hill Climb in Pennsylvania.

Chadwick campaigned its supercharged “Big Six” in the 1908 Vanderbilt Cup Race and, according to the October 29, 1908, edition of “The New York Times,” the vehicle “… showed exceptional speed both in practice and in the early part of the race.” Magneto trouble sidelined the Chadwick, according to “The NYT,” but they speculated that it would’ve likely challenged Locomobile for the overall. Hill climbing seemed to be the supercharged engine’s forte, and the Chadwick went on to win the 1908 Wilkes-Barre Hill Climb in Pennsylvania.

In discussing SUPERCHARGING BOOSTS FREE HORSEPOWER, McNessor focuses on the following types of superchargers: AXIAL-FLOW, CENTRIFUGAL, below, ROOTS, right, ROTARY SCREW, and VANE-TYPE, above. Hot rodders and drag racers are probably most familiar with Roots-type positive displacement blowers, while vintage and classic car enthusiasts can relate to centrifugal, vane-type, and even the iconic Latham axial-flow superchargers.

Continue reading SUPERCHARGING BOOSTS FREE HORSEPOWER @https://www.hemmings.com/stories/some-of-historys-greatest-performance-legacies-were-built-on-boost/

Continue reading SUPERCHARGING BOOSTS FREE HORSEPOWER @https://www.hemmings.com/stories/some-of-historys-greatest-performance-legacies-were-built-on-boost/