No other track on the Cam-Am schedule offered sweet corn and bratwurst like the little food stand at Elkhart Lake. Everyone on the circuit looked forward to it. The stand remains there today, just behind the main bleachers near the Start/Finish line.

Wisconsin sweet corn was roasted on an open grill and sold hot on a stick. The brats weren’t wrapped in a traditional bun; instead, they were served with mustard and sauerkraut on a homemade roll. The scent wafted through the stands and into the newly paved pit area that allowed Can-Am crews to work in something other than grass and mud for the first time.

The next stop on the series schedule was August 27, 1972 at Road America. The entire Penske team anxiously awaited the race knowing that the four-mile track’s enormous straightaways were perfectly suited to the L&M Porsche’s twin turbochargers.

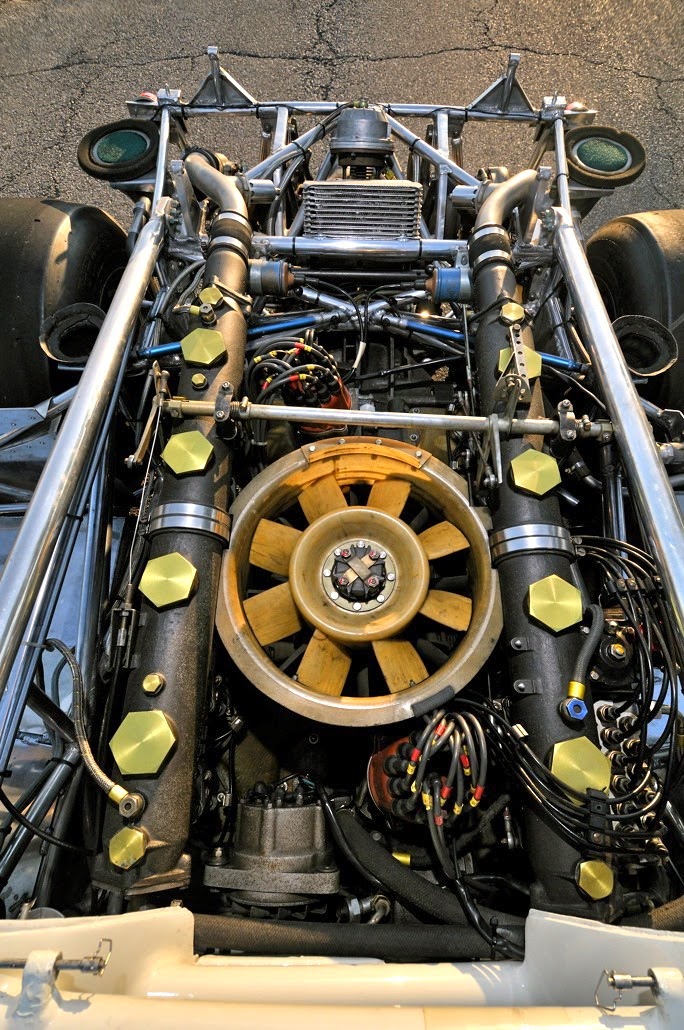

This car was among the most powerful racecars in the history of the sport. Bruce Canepa, whose restoration facility prepared the L&M Porsche for Rennsport IV in 2011, said that Porsche consistently underrated the horsepower of its cars in the 1970s.

Rumors have abounded for decades regarding the L&M Porsche’s power rating. Some sources claimed 800 horsepower while others claimed 900 or even more than a thousand. But the truth was constantly fluctuating and may never be known with certainty.

The L&M Porsche was never intended to have a single engine that could be gauged for an objective, simple answer. A number of engines were fitted into 917/10-003. Many times even driver George Follmer didn’t know the exact size of the latest engine to be received from Porsche.

“They’re always making things better at Porsche. That’s their DNA,” Follmer said. “A lot of times I don’t think the mechanics knew if it was a 5-liter or a 5.4-liter engine that they were putting in. When Porsche sent an engine, it just bolted up like the last one. I’m not sure we would have known if it had been a higher capacity engine because they hooked up just the same.”

Chief mechanic John “Woody” Woodard wasn’t so sure. “I thought we only had five-liter engines. Could they have snuck in a 5.4 at the end of 1972? Possibly, but not to my knowledge.”

Official Porsche records claim that the upgraded 5.4-liter engine was not installed in 917/10-003 until July 22, 1973. Then again, Porsche and Team Penske were known to deflect any serious questions and mislead wherever possible. Journalist Pete Lyons said, “They discourage prying eyes with tarpaulins, flatly refuse to answer certain questions, and are positively rude to photographers.”

Either way, Porsche considered the project in a constant state of evolution and changes in both Germany and at the Penske shop stateside were the rule rather than the exception.

Perhaps the most accurate barometer of the car’s legendary horsepower rating comes from Porsche restoration expert Bruce Canepa who said when the turbochargers on the L&M Porsche kick in, “it’s like getting punched in the back of the head.”

Canepa, whose company specializes in Porsche racing engines, estimates the output of the L&M Porsche at 1,100 horsepower in race trim and over 1,200 horsepower in qualifying trim with full turbo boost. Follmer remembered:

“It was a different kind of car. It was a short wheelbase with a lot of very sudden power. You went from almost nothing to eight or nine hundred [horsepower] in an instant.

It was twitchy and it didn’t like high-speed corners. It was fine in the tight stuff but it was not a comfortable car in high-speed corners. You kind of had to walk it through corners and it took some learning.

I didn’t know that car until probably the third or fourth race. It had handling characteristics that were… well… different, and as a driver, not always how you’d like it.

But you have to deal with it because that’s what it is. I had to learn how to cope with the sudden power. It was just a learning curve.”

In late-August, Follmer was attempting to qualify for the California 500 Indycar race at Ontario Motor Speedway when difficulties with the car forced the team to withdraw. Without sufficient time to repair the Indycar for the California race, Follmer left Ontario and took a private jet to Wisconsin, arriving the next day.

It rained during Follmer’s Can-Am qualifying run so rather than push his luck and risk the car, he settled for 13th position on the starting grid. It made little difference.

The L&M Porsche’s incredible V-12 engine was perfectly suited to Elkhart Lake, which offered one of the longest front stretches in North American racing.

The event droned on for 50 laps, but the race was over quickly. Follmer took the lead on the second lap and never looked back. The L&M Porsche gobbled up Road America’s long straightaways with a vengeance. Follmer flew past his competitors, lapping the entire field and taking his third win in the last four races. The L&M Porsche had hit full song and it was a sight to behold.

His memories of the day demonstrate just how dominant the L&M Porsche had become. “When it came time for the race it was dry and I think it took me two laps to take the lead. I had fun for a while. Then it kind of got boring.”

On September 17th the series moved to Donnybrooke road course (now Brainerd International Speedway) in Minnesota.

The new 917/10-005 chassis had arrived and been fully prepped for Mark Donohue’s return to racing. “6” was Donohue’s race number, so the 005 car was duly painted as #6 while Follmer’s 003 car was repainted as #7. Photographs taken after mid-September 1972 will show Follmer to be driving a #7 car; however, this is the same chassis he had been racing since Road Atlanta. The race number change was cosmetic and only done to give Donohue his favorite number again. George Follmer didn’t change cars; he only changed numbers.

Donohue and Follmer qualified side by side on the front row at Donnybrooke and the event appeared to be a repeat of Porsche’s landslide victory at Road America.

The team’s plan was for Donohue to win and gain enough points to make a run at second place in the overall season standings while Follmer would run second and continue his march toward what now appeared to be an inevitable Can-Am title.

The plan went down the drain when Donohue suffered a flat tire halfway through the event and retired. At that point, Follmer put his foot to the floor and began lapping the field.

The team had installed a small, additional fuel tank to account for the eternally long straightaway at Donnybrooke that ended in a banked, high-speed first turn that Can-Am cars took nearly flat out. Donnybrooke was an outrageously fast three-mile racetrack with a one-mile straightaway. Even the slowest corners would sustain speeds well over 75 mph.

Follmer spent much of every lap with the accelerator flat on the floor and both turbochargers devouring obscene amounts of fuel. To this day he questions the team’s decision not to bring him in for a pit stop, dial the turbo boost down, and send him back out in fuel-saving mode. There was certainly sufficient time to make any pit stop they wanted.

At the moment he ran out of fuel, the L&M Porsche was two laps ahead of everyone. Follmer recalls waiting helplessly along the side of the racetrack and watching the field pass by for two full laps before he finally lost the lead.

“Our performance at Donnybrooke was superb until we didn’t have enough fuel,” Follmer said. “We weren’t very proud that we screwed up so bad. We knew [our fuel situation was] marginal and we had put in an extra tank, but there wasn’t a lot of room where you could put a tank. But we missed it by a mile and a half.”

Still, Follmer placed fourth overall and continued to solidify his ironclad grip on the Can-Am Challenge Cup.

The final three races of the 1972 season were all held in October, with Edmonton being slated for Sunday the 1st. The plan stayed the same. Donohue was to win, with Follmer running second in order to gain a one-two finish in the season points championship for Porsche.

All was going according to plan until Follmer suffered a flat tire that put him over a lap behind the leaders. Donohue went on to win the event with a 46-second advantage over Denny Hulme’s McLaren M20, which put up a stiff fight. McLaren still hadn’t given up on their season.

Follmer called the M20 “a well-engineered car. It really was. It was a good car and it was fast. I’ve driven one, and McLaren really built a quality car.”

Nevertheless, Porsche would have easily taken a one-two finish had Follmer not suffered the same fate as his teammate in the prior event. A right rear tire was punctured early in the event and sportscar teams in 1972 weren’t structured to accommodate quick pit stops. The lengthy spell on pit road ruined what would have been another dominating performance by the L&M Porsche. Even after the flat tire, Follmer stormed back through the field to take third place.

A win at the October 15th event at Laguna Seca would secure enough points to assure Porsche and Penske the Can-Am Challenge Cup.

“At that point it was just a matter of time,” Follmer recalled. “The Captain decided to make sure I won the race in Monterey. We were supposed to run one-two, but I was supposed to win because that clinched the championship.”

The race was a formality. Donohue and Follmer qualified together on the front row and finished first and second according to plan, with Follmer winning and clinching the title.

Follmer was gracious in victory lane, calling Donohue to the podium and insisting that he celebrate with a drink of champagne. “We got along really well,” Follmer said in response to rumors that he and Donohue were occasionally at odds. “He was a friend. We joked together and got along just fine.”

Two weeks later, on October 29th, the season came to a close with the 15th annual Los Angeles Times Grand Prix at Riverside International Raceway. Follmer was more relaxed. The championship was already won and he could enjoy the experience without any pressure for points.

The Riverside road course was virtually flat and offered excellent visibility to spectators from any seat. The garage area was described by one fan as “carports with tin roofs and garage doors.” The dust and desert heat were intense and drove everyone – fans, teams and drivers alike – toward anything resembling shade.

Marilyn Motschenbacher Halder said, “They had a covered snack bar where everybody would go get ice because it was so hot out there. The snack bar had a very large open area. So a lot of people would gather there to sit and get a breeze, even though it was a dusty breeze sometimes. And you’d get a cold drink of water or glass of ice.”

The Riverside scoring tower was downright comical. It looked like an old fire tower, complete with a square girder system and a narrow, exposed staircase that promoted acrophobia even among the hardiest souls.

A four-sided sign proclaiming “Riverside” crowned the scoring tower, but the second “r” was missing from the side facing the main grandstands. Instead, it welcomed race fans to “Rive side.”

The final race of 1972 was well attended. Photographers lined the front straight and fans crowded into the last remaining grandstand seats. Thirty-four entries showed up making Riverside one of the largest fields of the season.

McLaren made one last, desperate effort to salvage their season with a win at Riverside. Denny Hulme’s M20 was outfitted with an enormous 9-liter Chevy engine producing over 800 horsepower. It was extremely fast. Hulme came within three-tenths of Follmer’s time in practice, enough to qualify in second position and bump Donohue back to third on the starting grid.

For Team Penske, the plan to have a one-two finish once again went awry. Donohue was supposed to win the race with Follmer second so as to gain as many points as possible for Porsche.

“It wasn’t really team orders,” Follmer said of Penske’s strategy. “We were trying to accomplish something for Porsche. That’s what they were paying for and that’s what they wanted us to do. We were doing our job and that was the important thing.”

But mechanical issues pushed Donohue out of contention for the win and Follmer was forced to carry the Porsche banner alone.

Denny Hulme once again drove hard but ultimately had nothing for the Penske machine. Eventually his oversized Chevy gave up and he pulled in after 45 laps. The L&M Porsche was simply too much for the McLaren M20, even in the hands of great drivers like Hulme and Revson.

This time, Follmer drove the Porsche into victory lane himself, stopping in the pits to pick up Heinz Hofer, Greg Syfert and John Woodard. All three mechanics sat on the side pods with Woodard carrying the checkered flag during their triumphant cruise to the podium.

Follmer stood in the cockpit sipping champagne with the race queen as the huge, three-foot silver Can-Am Challenge Cup was placed behind him. It was the exclamation point on a successful year.

The season was over. The parties had begun. The team was living in the moment and didn’t yet realize that they had made motorsports history.

To Be Continued.

Photos: David Newhardt/Mecum Auctions.

Stephen Cox is a racer and co-host of TV coverage of Mecum Auctions (NBCSN), sponsored by: http://boschett-timepieces.com/

http://www.mcgunegillengines.com/