Triumph took the world by storm in 1938 with its its Speed Twin, the first of the great British parallel twin street motorcycles. But their enthusiasm – and sales – were cut short by World War II, which began the following September.

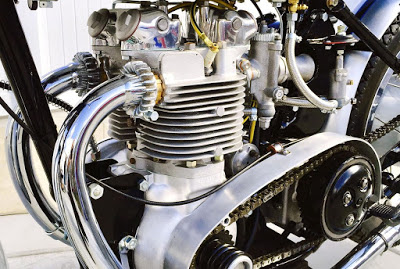

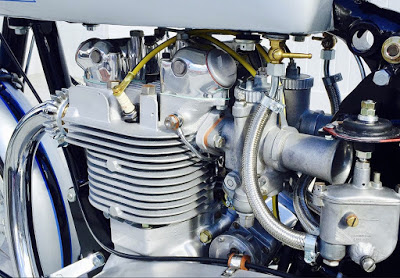

Triumph engineers quickly adjusted to wartime production by re-designing the Speed Twin’s excellent 500-cc power plant as a portable generator for military use. The cylinder heads and barrels were cast from aluminum and the generator’s operating temperature was kept in check by connecting an external fan to the engine’s handcrafted tin cooling shroud.

The generators were used in aerial combat to power equipment inside the Royal Air Force’s legendary, four-engined Lancaster heavy bomber. They were also dropped by parachute to British soldiers on the front lines. At the end of World War II, Triumph had a surplus of generators but no motorcycles to sell. Once again, the company adapted to the situation.

“After the war there were no race bikes because most of the manufacturers were building tanks, or whatever,” said AMA Motorcycle Hall of Fame member Gavin Trippe. “Triumph built a generator that was carried in the war on bombers, or parachuted in to troops. It had to be lightweight, compact and high performance. After the war, while working on its next generation of bikes, Triumph built 150 motorcycles fitted with their generator motors.”

Extraordinarily rare today, these generator-powered motorcycles became known as Triumph Grand Prix “Square Barrels.” Ernie Lyons rode one to victory at the 1946 Manx Grand Prix, inspiring Triumph to build a handful of the bikes throughout the late-1940s.

“The reason its called ‘square barrel’ is because it had to be compact and it had cooling shrouds around it,” Trippe continued. “Some of them were raced. One of them ran in the Isle of Man with a generator motor. Some came to the United States where they ran the Daytona Beach races. They were adapted to have crankcase covers on them because of the sand. Some competed in the International Six-Day Trial in Italyand won the manufacturer’s gold medal.”

“But because they were sort of stop-gap measure, they were not important,” Trippe said. “They were just used to fill a hole while Triumph developed their next line of street bikes. The bottom line is that once the new Triumphs became available, these were irrelevant. So they were trashed, they were swapped around, beaten up and in the end, just thrown away. Nobody kept one from the factory and said, ‘This will be worth a lot of money one day.’”

Which is a shame, because only ten to twenty of these magnificent motorcycles are still believed to exist, of which perhaps half a dozen are in running condition. If you are lucky enough to find one of them today, be prepared to pay at least $30,000 to take it home. The few surviving examples represent a wonderful combination of motor racing history, British ingenuity and the legacy of aviation in World War II.

Stephen Cox is a racer and co-host of TV coverage of Mecum Auctions (NBCSN), sponsored by http://www.mcgunegillengines.com/ http://www.boschett-timepieces.com/index.php