He wasn’t the first to try, nor was he the last. Armed with a huge budget, a massive turbine engine and two of the finest drivers on the planet, in the spring of 1968 Carroll Shelby was ready to steal the Indianapolis 500.

The plan was straightforward. Ken Wallis, a 38-year-old British aircraft engineer, had designed the famed Granatelli-Lotus Turbine with which Parnelli Jones had nearly won the race in 1967. Wallis had left Granatelli’s team and was now looking for work. Shelby hired Wallis to build the team’s racecars, and then hired reigning Formula 1 champion Dennis Hulme and defending Can-Am champion Bruce McLaren to drive them.

On paper the team appeared unbeatable. So confident was Shelby, above, talking to Wallis, that he told a reporter, “They are the nearest to certain winners ever built in the history of the race.” That was, until the United States Auto Club changed the rules.

Turbine engines rely on air intake to create power. A wider air intake, “annulus”, permits enormous horsepower, while limiting the annulus has the opposite effect. After the wild success of Granatelli’s STP turbine in 1967, USAC was faced with a difficult decision. The sanctioning body could continue to allow turbine machines to dominate the race and effectively render traditional piston-powered cars obsolete, or they could try to level the playing field by limiting turbine power. They chose the latter. In doing so, USAC violated a long-standing policy that prohibited year-to-year rule changes and guaranteed that newly built machines could compete for at least two years between regulatory adjustments.

During the car’s construction in late 1967, Wallis had been told by USAC Competition Director Henry Banks, “there’s no question in my mind they will pass inspection.”

But the game changed dramatically when USAC announced that the annulus inlet for turbine engines in 1968 would be dramatically reduced from 24 inches to 16 inches. Instead of producing a blistering 1,300 horsepower, the General Electric T58 turbine engine used in the Shelby/Wallis cars would be severely limited.

The pressure on the team mounted. Engineer David Norton worked in the team’s Torrance, CA fabrication shop and recalled, “In a race, the deadlines are absolute. You’re either ready to go or you’re not. We were under that kind of pressure the whole time.”

After three days of working around the clock in early 1968, engine tests were conducted and the car was put through its paces on the road course at Riverside and the oval at Phoenix.

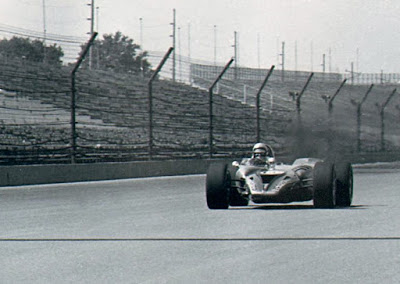

The cars were shipped to Indianapolis in March, where the first test with driver Bruce McLaren, below, produced speeds of only 158 mph. Pole speeds were projected to be over 170 mph, meaning that the much-vaunted Shelby/Wallis Turbine would be lucky to qualify for the race at all, let alone win it.

McLaren’s comments were unflattering. “It’s a bit like a cross between a Sherman tank and a Formula Ford.” It was clear that while the new 16-inch restriction on the turbine engine was the primary problem, it was by no means the only problem.

Visually, the car appeared trim and balanced. But the scales showed that the Shelby/Wallis Turbine was obese. Original calculations estimated its final weight at a competitive 1,400 pounds, but in full fighting trim it bloated to nearly 1,800 pounds. The additional weight affected everything from braking to cornering to acceleration.

Ken Wallis was running out of time… (CONTINUED in our next blog, Part 2 of 2)

Stephen Cox is a racer and co-host of TV coverage of Mecum Auctions (NBCSN), sponsored by: http://www.mcgunegillengines.com/

http://www.boschett-timepieces.com/index.php